Sunday, March 26, 2006

Saturday, March 18, 2006

from the dark side

Went to a class today at the Sydney Taxi School as part of the requirements to renew my licence. It's interesting to spend a day in a room full of Turks, Bangladeshis, Chinese, Iraqis and so on, especially since these classes are fairly perfunctory so far as actual learning is concerned. Or, the learning consists more of listening to stories than it does absorbing information. You always end up talking about security issues in a group of cab drivers. One guy had a shocker to tell. He was driving in the St. George area, in the south of the City, not long after the Cronulla riots. It was one or two in the afternoon. He was hailed by a woman with bags, pulled over, popped his boot, got out to help her with her bags. As he was bending down to pick them up, he was set upon from behind by two or three guys - he wasn't sure how many, because they knocked him half conscious (with some kind of, again unknown, implement) then started kicking him when he was down. He surmised it was a racist attack because he heard the abuse they were shouting as they hurt him, calling him a wog. This guy had recently been stitched up after an operation to his stomach - they undid that. He had to have his nose rebuilt. He still has a bruise under one eye, three months later. He doesn't know how he got home but assumes that he somehow drove. His wife took him to hospital. He can't work and he said his kids start to cry if they even hear the word taxi. And this happened to him, with malice aforethought, purely because of his appearance. He said he looked around as he got out of the cab but saw no-one; the police later suggested the guys waiting were hiding under a car (!) Don't know what his background is, he didn't say. Perhaps Turkish, his friend, next to him, who knew the story, was. The guy taking the class said he looked Italian. I just thought he looked like an Aussie. But, no. But, yes.

Friday, March 17, 2006

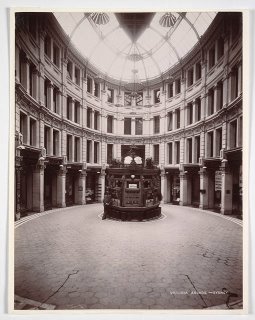

QVB

Luca Antara, the book, tarries a while in the QVB, because, when I first came to Sydney, that's where the Public Library was. I was interested in telling a brief version of its history but as I was in New Zealand when I wrote that section, I got my material on-line. Now, preparing the Notes on Sources, I find that there is a book about the Grand Dame. The Queen Victoria Building 1898-1986, by John Shaw with photos by David Moore (among others), was written at the initiative of architects Stephenson & Turner, who carried out the restoration of the building in the 1980s. Lovely book. One of its glories is the archival photographs, which are not restricted to the building itself but cover many aspects of Sydney's CBD down the years. I was fascinated by the pictures of arcades, most of which were demolished before I came here. The Imperial Arcade, which resembled a theatre set; the Victoria Arcade, with its elliptical glass dome; the Royal Arcade with its Roman and Florentine echoes. Only the Strand Arcade now remains, along with the QVB itself which, although it is a free standing building, has many affinities with arcade buildings, for example, its glazed barrel vault roof.

I can't remember now where we'd been - perhaps to a concert or a gig - I do recall one night, late, wandering with my then wife into the newly restored QVB, which was wide open, brightly lit and vastly empty; this was before the shops had been tenanted or opened. There was distant music coming from the upper levels. We walked into each other's arms and waltzed together along the tiled floor of the promenade known as the Avenue. This floor slopes, there's a slight hill running down Market Street towards George Street, probably the old bank of the Tank Stream, and the makers of the building followed that fall. I'm no longer sure either if it was the same night or another - probably the same - that, climbing the stairs we found, on the top-most level, a function or celebration of some kind going on. Passing across the floor we encountered Barry Humphries, so shickered he could not stand up, being escorted, like an ocean liner by tugboats, by two gorgeous young women from one revelry to another. Or perhaps from revelry to bathroom.

After finishing the book I went and had another look at the QVB, and at the Strand Arcade. Beautiful structures, beautifully restored (Stephenson & Turner did the Strand as well), yet I couldn't help feeling a slight pang of disappointment. Why? I think it's just the dullness of the use they are put to, at least from my point of view. I can remember being absolutely fascinated by the arcades in Auckland in the 1970s, because of the strange variety of shops, businesses and other organisations you found there: erotica, philately, obscure foreign friendship societies, fortune tellers, dance academies and who knows what else. Whereas now what you find is the relentless shininess of contemporary consumer culture. Many wonderful things are there which you can buy if you want, but something else is lacking, perhaps aura, perhaps grime, perhaps a whiff of the disreputable. The QVB replaced the George Street Markets and was built as a market itself. In its early days it attracted palmists and mind-readers along with teachers of music, art and dance. Now mostly what you find are handbags, hand lotions, hand made chocolates. It'd be an awful confession to say that I preferred the QVB derelict and that isn't quite what I mean. I just wish there was less shininess, more texture, some fluid and chaotic tactility there.

Monday, March 13, 2006

RuneScape

Had a good time with my kids this weekend. Or, should I say, they had a good time with me? Partly it was because Jesse's friend Monty came over Saturday night for a sleepover. Kids like being in a pack, even three is better than two. At one point we went over to the local park for an hour or so. It was early evening; tennis on the courts, skate-boarders and bike riders on the skate-board rink, smaller kids on the equipment and the littlies in the fenced off playground; a soccer game featuring, I noticed, two of the guys from the local liquor shop. At one point Liamh, who's obsessed with them, found a stash of sticks behind a tree on the far edge of the park and enlisted the other two in a game. I watched it from a bench on the other side, far too far away to hear anything or see detail. They were big, robust looking sticks, thick and long; but the boys seemed to be using them not as weapons but as ... I don't know? Wands? Their movements had an hieratic quality, they held them gesturally and moved them slowly through the air. It looked like a dance and went on for quite a while, quarter of an hour maybe. Then, all of a sudden, they laid them down (behind another tree, for later perhaps) and came tearing back across the park towards me. As we were walking home I asked what they'd been doing. Orrh, said Jesse, We were playing Runescape. He didn't expatiate and I didn't ask. Runescape's huge among the kids and it seems like a different sort of game from the usual shoot 'em up, bang 'em down. My boys don't play it here much because it requires a PC for its full range to be available and I'm on a Mac; when they do I'm impressed by the contemplative air that comes over the flat. One day this weekend I watched them build a canoe and sail it down a river. Another time, I recall Jesse telling me he knew how to fletch arrows. He described the process in great detail and then allowed that, yes, they were virtual arrows. This is a game where groups form and play against/with each other; some of these groups are very large and, it goes without saying, they are multinational. I'm intrigued ... but not as intrigued as I was by the stick game I saw across the park the other evening.

Friday, March 10, 2006

Once on Chunuk Bair

Am I getting sentimental in my old age? The other morning, just after I woke up, I felt the need to check some geographical details with respect to the Gallipoli peninsular. I was trying to understand the precise relationship between Lone Pine, Chunuk Bair and the Nek. Also, which were the troops that took the first, and the second, though only briefly, and were slaughtered in their hundreds at the third site. Was it simply the sound of the names in my head, on my tongue, that blurred my eyes, so that I could not read the words on the page? It was strange to lie back on the pillows and feel the tears running down my cheeks - why?

Sunday, March 05, 2006

badman

As anyone who has ventured there knows, Ern Malley Alley is a hall of mirrors, an infinite regression, a world of answers without questions and questions lacking answers. You go there at your peril and if you will be so bold or so foolish, you need allies: a sense of humour, an unimpaired sceptical sense, what Keats called negative capability ... anyway. Something I hadn't quite considered when I entered the labyrinth was that I would be dealing with my father's generation, obvious as that might seem. He was born in 1920, the second of three brothers. Ern Malley was born in 1918, the 14th of March, Einstein's birthday; James McAuley in 1917, Harold Stewart in 1916 ...

Another thing I did not anticipate is that I would find myself wrangling with the ghost of Don Bradman (b. 1908). How did this happen? Well, partly it's simply local history: the boy from Bowral made his first century in Sydney grade cricket just down the road from here, at Petersham Oval (there's a plaque), which means it's at least possible that Ern, who grew up in the area, was there that November day. Partly, too, it's because if you read Australian history between the wars, you simply can't escape the Don. He is ubiquitous. So that, a few weeks ago, I went to the Ashfield library and brought home a couple of books, one of which, written by an Englishman as social history as well as sporting biography, was so good that I read it cover to cover in a matter of days. Now, coincidentally, I've just watched the second instalment of a two part television documentary on ABC, which covers the same ground as the book and even interviews its author. So what have I learned?

Well, it's an emotional minefield. And very personal. My father loved two sports, rugby and cricket. He'd played both, with some skill, in his youth, coached school teams while he was teaching, later on spent a lot of time listening to games on the radio or watching them on television. I inherited these enthusiasms from him and maintained them during his long decline partly so as to have this neutral common ground where we could always go when we talked. Now he's gone I don't know why I keep them up because the actual sporting culture as it has evolved, mostly disgusts me. That's one thing. The second thing is the intimate relationship between Australian life and sporting prowess. Much has been made of the fact that Bradman's prodigious feats as a batsman began during the Great Depression and that for many people living in penury and misery, he became a kind of secular saviour ... this strange contract, between sporting success and the pride of individuals in themselves, is not confined to Australians but they - we - are certainly paragons in its expression. As an expat New Zealander who is an Australian citizen, I express this fanaticism in reverse, taking no pleasure in Australian wins and great delight in their unfortunately rare losses. Weird, huh?

But, Bradman. The great hero of the common man, and a common man himself ... except he wasn't. He was a protestant in a land of Irish Catholics, a teetotaller in a country of drinkers and drunks, he played the piano and listened to classical music, in the evenings after a day's play, instead of celebrating with his mates, he'd go to his room and write letters or read books. And get an early night. He was also a Royalist in a culture that at least fancies itself to be 'naturally' Republican, he earned his living as a stock broker and wasn't above taking financial advantage of circumstances when he could see a way to do so - when, in 1945, his boss in Adelaide informed the Stock Exchange he could no longer meet his commitments, Bradman had taken over the office and hung his shingle out within 36 hours of the declaration, apparently with the consent of the receiver. In some of this, he shows a character not unlike that of my paternal grandfather, who was all of those things: protestant, teetotal, royalist, businessman, devious, a sporting fanatic - and Australian; most of this description also fits the present Australian Prime Minister, John Howard (I don't believe he is teetotal). The other thing the three men - Bradman, my grandfather, Little Johnny - have in common is their ruthlessness.

As we know, sport is a surrogate for war and despite all the waffle about playing the game, you can't really engage in it without a determination to win. Afterwards you may fraternise with your opponents but while the game's on you have to be prepared almost to kill. In our peculiar culture, that analogy with war does extend to business and to politics, but with this difference: the wins and losses are real, there are real victims, real casualties, real deaths. Bradman's extreme ruthlessness as a cricketer, later as Australian captain, was mostly visited upon the English, whom he took great delight in humiliating howsoever and whenever he could; but there was no contradiction with his Royalism or his Empire Loyalism, because it was just a game. For precisely the same reason, sport/war is a very bad analogy for business and politics, but pervasive nevertheless. Watching Little Johnny bask in the approbation of the local version of the great and the good during his ten year anniversary celebrations made me realise that he has a conscience white as the driven snow, as they say, most likely because he's left all that behind on the playing field. Watching the obsequies for Kerry Packer, that superlative sporting man, the other week led to the same conclusion. For these kinds of people, the end does justify the means and the end is, in the end, very simple: to win.

My father set himself against his father and attempted to live an ethical life; it ended in alcoholism, loneliness and despair, with one of his few consolations, the rugby or the cricket on the TV or the radio. This doesn’t mean that he made the wrong choice and nor is it sufficient to ascribe his fate to that choice: of course not, there were a lot of other factors involved, which I can’t go into here. But it was a conscious choice: the poetry he wrote in his youth he abandoned in order to dedicate himself to a form of social action which would make a real difference to peoples’ lives and in this he was remarkably successful; the visits he sometimes got from those he had taught were another of his consolations.

Ern Malley didn’t have to live with the consequences of his dedication to poetry, though both James McAuley and Harold Stewart did. Sometimes I imagine Malley as a kind of Anti-Bradman, feckless where the other was conscientious, ironic rather than sincere, profligate not abstemious, raucous not calm, unsporting, twisted, decadent, sardonic, rude … but of course he wasn’t an Anti-Bradman so much as an Anti-Everything: everything, that is, that could not be fitted into the world view of two gifted yet resentful men, both self-hating, one of whom became a Catholic conservative academic, the other a scholarly Buddhist monk. As for Bradman, he lived to a ripe old age and was, so far as one can tell, kind to his old opponents - but never forgave his enemies. I understand John Howard is a great hater too.

Another thing I did not anticipate is that I would find myself wrangling with the ghost of Don Bradman (b. 1908). How did this happen? Well, partly it's simply local history: the boy from Bowral made his first century in Sydney grade cricket just down the road from here, at Petersham Oval (there's a plaque), which means it's at least possible that Ern, who grew up in the area, was there that November day. Partly, too, it's because if you read Australian history between the wars, you simply can't escape the Don. He is ubiquitous. So that, a few weeks ago, I went to the Ashfield library and brought home a couple of books, one of which, written by an Englishman as social history as well as sporting biography, was so good that I read it cover to cover in a matter of days. Now, coincidentally, I've just watched the second instalment of a two part television documentary on ABC, which covers the same ground as the book and even interviews its author. So what have I learned?

Well, it's an emotional minefield. And very personal. My father loved two sports, rugby and cricket. He'd played both, with some skill, in his youth, coached school teams while he was teaching, later on spent a lot of time listening to games on the radio or watching them on television. I inherited these enthusiasms from him and maintained them during his long decline partly so as to have this neutral common ground where we could always go when we talked. Now he's gone I don't know why I keep them up because the actual sporting culture as it has evolved, mostly disgusts me. That's one thing. The second thing is the intimate relationship between Australian life and sporting prowess. Much has been made of the fact that Bradman's prodigious feats as a batsman began during the Great Depression and that for many people living in penury and misery, he became a kind of secular saviour ... this strange contract, between sporting success and the pride of individuals in themselves, is not confined to Australians but they - we - are certainly paragons in its expression. As an expat New Zealander who is an Australian citizen, I express this fanaticism in reverse, taking no pleasure in Australian wins and great delight in their unfortunately rare losses. Weird, huh?

But, Bradman. The great hero of the common man, and a common man himself ... except he wasn't. He was a protestant in a land of Irish Catholics, a teetotaller in a country of drinkers and drunks, he played the piano and listened to classical music, in the evenings after a day's play, instead of celebrating with his mates, he'd go to his room and write letters or read books. And get an early night. He was also a Royalist in a culture that at least fancies itself to be 'naturally' Republican, he earned his living as a stock broker and wasn't above taking financial advantage of circumstances when he could see a way to do so - when, in 1945, his boss in Adelaide informed the Stock Exchange he could no longer meet his commitments, Bradman had taken over the office and hung his shingle out within 36 hours of the declaration, apparently with the consent of the receiver. In some of this, he shows a character not unlike that of my paternal grandfather, who was all of those things: protestant, teetotal, royalist, businessman, devious, a sporting fanatic - and Australian; most of this description also fits the present Australian Prime Minister, John Howard (I don't believe he is teetotal). The other thing the three men - Bradman, my grandfather, Little Johnny - have in common is their ruthlessness.

As we know, sport is a surrogate for war and despite all the waffle about playing the game, you can't really engage in it without a determination to win. Afterwards you may fraternise with your opponents but while the game's on you have to be prepared almost to kill. In our peculiar culture, that analogy with war does extend to business and to politics, but with this difference: the wins and losses are real, there are real victims, real casualties, real deaths. Bradman's extreme ruthlessness as a cricketer, later as Australian captain, was mostly visited upon the English, whom he took great delight in humiliating howsoever and whenever he could; but there was no contradiction with his Royalism or his Empire Loyalism, because it was just a game. For precisely the same reason, sport/war is a very bad analogy for business and politics, but pervasive nevertheless. Watching Little Johnny bask in the approbation of the local version of the great and the good during his ten year anniversary celebrations made me realise that he has a conscience white as the driven snow, as they say, most likely because he's left all that behind on the playing field. Watching the obsequies for Kerry Packer, that superlative sporting man, the other week led to the same conclusion. For these kinds of people, the end does justify the means and the end is, in the end, very simple: to win.

My father set himself against his father and attempted to live an ethical life; it ended in alcoholism, loneliness and despair, with one of his few consolations, the rugby or the cricket on the TV or the radio. This doesn’t mean that he made the wrong choice and nor is it sufficient to ascribe his fate to that choice: of course not, there were a lot of other factors involved, which I can’t go into here. But it was a conscious choice: the poetry he wrote in his youth he abandoned in order to dedicate himself to a form of social action which would make a real difference to peoples’ lives and in this he was remarkably successful; the visits he sometimes got from those he had taught were another of his consolations.

Ern Malley didn’t have to live with the consequences of his dedication to poetry, though both James McAuley and Harold Stewart did. Sometimes I imagine Malley as a kind of Anti-Bradman, feckless where the other was conscientious, ironic rather than sincere, profligate not abstemious, raucous not calm, unsporting, twisted, decadent, sardonic, rude … but of course he wasn’t an Anti-Bradman so much as an Anti-Everything: everything, that is, that could not be fitted into the world view of two gifted yet resentful men, both self-hating, one of whom became a Catholic conservative academic, the other a scholarly Buddhist monk. As for Bradman, he lived to a ripe old age and was, so far as one can tell, kind to his old opponents - but never forgave his enemies. I understand John Howard is a great hater too.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Houses of the Poets

It's never quite clear to me what is to be gained by going to look at houses where known people were born, grew up or at some stage lived, which doesn't mean I don't sometimes do it. At the very least, I suppose, there is subsequently a memory trace where before was either a blank or something imaginary. Which isn't to say the imaginary isn't preferable, only that it will in most cases recede before the real. Anyway ... having learned from Michael Ackland's book Damaged Men the addresses of the houses where James McAuley and Harold Stewart grew up, and realised they are both within a few kilometres of here, I went today to look at them.

52 The Crescent, Homebush, McAuley's home from the mid 1920s until he left home during WW2, is a small brick Victorian villa in a now leafy street running parallel to the main western line just down the road from the Homebush shops. It's shabby and neglected now, it looks like it's rented out, but it was probably far more prepossessing and indeed, straight-laced, when it belonged to the McAuley family. Jim's Dad was a successful real estate agent which raises the question as to why he kept on living in this rather small house in this rather grim suburb with its stockyards and its abbatoir; on the other hand, according to Jim, he was a rather grim man.

Although McAuley remembered the scent of wisteria, there's now a small frangi pani tree outside the window of the bedroom next to the front door, which may have been his: At night he watched the dancing shadows created by the lights of passing trains on his bedroom walls and dreamed of unknown destinations, Ackland says. The most startling presence in the street is an enormous Gallipoli Pine growing behind the house, one of the largest I have seen. McAuley, born in Lakemba in 1917, may have come into the world contemporaneous with this tree and I took its sombre presence as a sign that he still haunts the neighbourhood.

Chowringhee, where Harold Stewart was born in 1916 and where he grew up, is or was at 31 Tavistock Street, Drummoyne: a short, also leafy street, running up hill from Drummoyne Park with its green oval, not far from Five Dock Bay. All three streets crossing Tavistock are now major traffic arteries so the area does not have the quiet gentility it did when Harold lived here. His father, who was in India until his early thirties and spoke fluent Hindustani, was the local health officer.

The house at #31 presented the same drab exterior as did the McAuley residence, though it was clearly a much larger place. However, it seems to have been divided at some point into a makeshift duplex; the name plate, if there ever was one, has disappeared and I did wonder, since the other half of the duplex was #33, if I had the right house. Perhaps the street had been renumbered at some point?

This is what Ackland describes: Tavistock Street was shaded by camphor laurels and small gardens set off the entrances to most of its serried brick houses. The drab exterior of the Stewarts’ home accorded ill with its exotic Indian name ... and its tastefully presented interior. A large rear veranda afforded easy access to a modest oasis of calm, with fernery, fish pond, vines and a spreading apple tree, while Marion (Harold's sister, younger than him by nine years) remembered home-life as characterised by ahimsa, or non-violence of thought and deed.

There was a bullish looking man in a large 4WD parked outside #31 with the talkback radio turned up loud in his cab and he gave me the leery eye when I turned the car around and parked across the road to get a decent look at the house, so I didn't hang around for long. Ackland also writes: ... in the 1920s the future poet could still wander along dusty, unmade roads lined with gumtrees and post-and-rail fences, reminiscent of country towns, and shimmering water was always close at hand.

In contradistinction to the grimness of McAuley's bedroom (ordered and impersonal, its furnishings kept to a minimum with a bed, dresser and bare walls), Harold's served as study, art studio and music room ... the bed, which doubled as a settee when friends called, had a deep blue coverlet shot through with muted gold thread and [the room] contained a large desk, ample library, music stand and gramophone, as well as a small table for displaying art works — making it the prototype of his successive dwellings.

The strongest impression I took away from both houses is perhaps paradoxical: they each in their different way reminded me of the house at 40 Dalmer Street in Croyden, Ern Malley's sister Ethel's house, where the imaginary poet spent his last few imaginary months. This house was, as they say in fact, owned by Harold's sister, the aforementioned Marion ... the other thing I glimpsed, though only in passing, was the uniformity of these lower middle class western Sydney suburbs between the wars, with their rows and rows of near identical houses made of liver coloured brick, their pubs and corner shops, their bare streets where the trees, if they had even yet been planted, had scarcely begun to grow.

52 The Crescent, Homebush, McAuley's home from the mid 1920s until he left home during WW2, is a small brick Victorian villa in a now leafy street running parallel to the main western line just down the road from the Homebush shops. It's shabby and neglected now, it looks like it's rented out, but it was probably far more prepossessing and indeed, straight-laced, when it belonged to the McAuley family. Jim's Dad was a successful real estate agent which raises the question as to why he kept on living in this rather small house in this rather grim suburb with its stockyards and its abbatoir; on the other hand, according to Jim, he was a rather grim man.

Although McAuley remembered the scent of wisteria, there's now a small frangi pani tree outside the window of the bedroom next to the front door, which may have been his: At night he watched the dancing shadows created by the lights of passing trains on his bedroom walls and dreamed of unknown destinations, Ackland says. The most startling presence in the street is an enormous Gallipoli Pine growing behind the house, one of the largest I have seen. McAuley, born in Lakemba in 1917, may have come into the world contemporaneous with this tree and I took its sombre presence as a sign that he still haunts the neighbourhood.

Chowringhee, where Harold Stewart was born in 1916 and where he grew up, is or was at 31 Tavistock Street, Drummoyne: a short, also leafy street, running up hill from Drummoyne Park with its green oval, not far from Five Dock Bay. All three streets crossing Tavistock are now major traffic arteries so the area does not have the quiet gentility it did when Harold lived here. His father, who was in India until his early thirties and spoke fluent Hindustani, was the local health officer.

The house at #31 presented the same drab exterior as did the McAuley residence, though it was clearly a much larger place. However, it seems to have been divided at some point into a makeshift duplex; the name plate, if there ever was one, has disappeared and I did wonder, since the other half of the duplex was #33, if I had the right house. Perhaps the street had been renumbered at some point?

This is what Ackland describes: Tavistock Street was shaded by camphor laurels and small gardens set off the entrances to most of its serried brick houses. The drab exterior of the Stewarts’ home accorded ill with its exotic Indian name ... and its tastefully presented interior. A large rear veranda afforded easy access to a modest oasis of calm, with fernery, fish pond, vines and a spreading apple tree, while Marion (Harold's sister, younger than him by nine years) remembered home-life as characterised by ahimsa, or non-violence of thought and deed.

There was a bullish looking man in a large 4WD parked outside #31 with the talkback radio turned up loud in his cab and he gave me the leery eye when I turned the car around and parked across the road to get a decent look at the house, so I didn't hang around for long. Ackland also writes: ... in the 1920s the future poet could still wander along dusty, unmade roads lined with gumtrees and post-and-rail fences, reminiscent of country towns, and shimmering water was always close at hand.

In contradistinction to the grimness of McAuley's bedroom (ordered and impersonal, its furnishings kept to a minimum with a bed, dresser and bare walls), Harold's served as study, art studio and music room ... the bed, which doubled as a settee when friends called, had a deep blue coverlet shot through with muted gold thread and [the room] contained a large desk, ample library, music stand and gramophone, as well as a small table for displaying art works — making it the prototype of his successive dwellings.

The strongest impression I took away from both houses is perhaps paradoxical: they each in their different way reminded me of the house at 40 Dalmer Street in Croyden, Ern Malley's sister Ethel's house, where the imaginary poet spent his last few imaginary months. This house was, as they say in fact, owned by Harold's sister, the aforementioned Marion ... the other thing I glimpsed, though only in passing, was the uniformity of these lower middle class western Sydney suburbs between the wars, with their rows and rows of near identical houses made of liver coloured brick, their pubs and corner shops, their bare streets where the trees, if they had even yet been planted, had scarcely begun to grow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)